In this five minute video ACM Training’s communication coach, Richard Uridge, talks about striking the right tone in presentations – in particular in the current climate with all that is happening in Ukraine.

Category: Presentation

G is for Gimmick

Using cheap tricks or stunts to grab an audience’s attention is the presentational equivalent of click bait. So here ACM Training’s communication coach, Richard Uridge, explains (with just a hint of festive irony) the difference between gimmicks and legitimate devices to hook people into your presentation. And, yes, you really won’t believe what he looks like today!

How a treasury tag might have saved the Prime Minister’s bacon

Every failure is an opportunity to learn and grow – even when you’re the British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson. And it’s to him that we dedicate this episode of the Z to A of Presenting: T is for Treasury Tag. Watch to find out how the PM could have saved himself a whole heap of grief in that lemon-chewingly embarrassing speech to the CBI with one of those little bits of string with a tiny metal bar at either end that are buried at the back of stationary cupboards everywhere. It could just save your next presentation from a #peppapig moment too!

PS Buy shares in treasury tags!

[products limit=”4″ columns=”4″ skus=”wpid=145, bookid=02″]

Things you can do with Zoom and never realised

We’re often asked how our Zoom and Teams meetings and training sessions here at ACM are funkier than most. So here’s the answer! Our chief geek (and media and communication coach) Richard Uridge runs through the kit we’ve put together to make our online courses visually stimulating.

[products limit=”4″ columns=”4″ skus=”wpid=145,bookid=01,wpid=142,bookid=02″]

The Z to A of Presenting: Z is for Zoom

The first in the “Z to A of Presenting” (because why start at A when everyone does)? In this Halloween-themed episode Richard Uridge explains how a simple sticky can help you keep your audience engaged. Watch to the very end if you want the full, scary surprise.

[products limit=”4″ columns=”4″ skus=”wpid=145,bookid=01,wpid=142,bookid=02″]

Wheely armed webinars? I hate them!

A lot of presentation skills trainers are saying we need to be much more animated presenting online via Zoom and MSTeams than was the case when working face-to-face. In this short clip I argue against such an approach. I reckon the skills of an online presenter are more like those of a screen actor than a stage actor. Smaller, more suble movements and facial expressions are the key. Not grand gestures for the people in the cheap seats at the back of a theatre auditorium. Why? Because you are in their face. Or certainly no further than an arm’s length away.

Don’t start with content when planning a presentation. It ain’t the first step!

Step away from the PowerPoint. Close the Keynote. When you’re preparing a presentation – online or face-to-face – resist the urge to start creating content too soon. It’s a receipe for failure. And a mistake too many of us make.

Unputdownable books and unlookawayable from presentations

Here I am murdering the English language and inventing at least two new words in my mission to help us all become better presenters. We should think of ourselves as storytellers and structure our presentations in the same way as a writer constructs and unputdownable book.

Why you should never ignore your audience

“If your presentation doesn’t work for your audience it won’t work for you.”

Richard Uridge, ACM Training

FF sake – what musical notation can teach presenters and public speakers

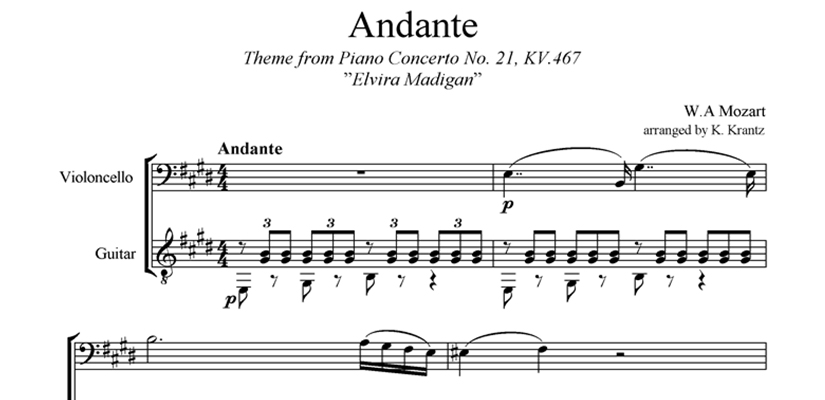

Mozart was a dab hand at the piano. Which is putting it mildly. A veritable child prodigy, by the age of five he was already performing for royalty. And by the time he died – at just 35 – he’d written 600 works including his Piano Concerto 21 shown above.

I mention all this because more than 200 years later Mozart’s music has something to teach us as presenters and public speakers. He knew how to captivate an audience with high notes and low notes. Fast sections and slower, more reflective sections. Louder bits and quieter bits. In short, he scored his compositions in such a way that made them captivating. And I’d argue that you should score your presentations to make them captivating.

Far too many of the presentations I’ve had the misfortune of sitting through wash over me. Not because the content is dull (although it may be) but because the delivery is dull and as a consequence the content, however important, fails to register.

“Blah, blah, blah…

Nobody uses these exact words, of course. But they do use words that when spoken by the same voice, at the same pace and the same tone end up sounding so samey they may as well be.

“…blah, blah, blah.

The net effect of which is to send the audience to sleep. So how can we turn our presentations from unintended lullabies into stirring sonatas?

[product sku=”wpid=21″]

TEMPO

Well let’s start with tempo. You’ll see the word “andante” appears above the bar at the beginning of the sheet music at the top of this post. This notation of Italian origin is an instruction that the movement or passage should be played at a moderately slow tempo. If the whole concerto was to be played at the same tempo it’d sound much less impressive. It’s the juxtaposition of different tempos that make each stand out and contribute to the overall effect. And so it is with presentations. What bits of your presentation are best delivered allegro – that is fast? And which sections might best be delivered adagio – slowly?

VOLUME

Back to that sheet music you’ll see the letter “p” appears under a couple of notes. This means that the note should be played piano or softly. Two ps together as in pp means the note should be played pianissimo or very softly. It seems counterintuitive but if you want your audience to take notice of a really important point, saying it more quietly than your usual presentational volume (p or pp in musical terms) forces them to listen more carefully and helps reinforce the point. Although not if you’re too quiet – ppp!

At the opposite end of the dynamic range are the effs – f, ff and fff. F stands for forte or loud. FF for fortissimo or very loud. And FFF for fortississimo meaning very, very loud. I’d avoid fff altogether as it can seem really rude and shouty unless done for special effect, in which case it’s probably best to forewarn the audience or, at the very least, explain immediately after the very, very loud passage why it was so. And even ff should be used sparingly as it’s tiresome to listen to permanently loud speakers.

The knack is to vary the volume in a pleasant sounding and naturalistic way just as we do automatically in conversation. Think of your presentation coming to a crescendo – another musical term that means increasing or, literally, growing. Build to a major point or a call to action.

REST

Look carefully at the sheet music above and you’ll see what looks like a fat or bold hyphen at the end. This is what’s called a rest (actually it’s a half rest but let’s not get too technical – this is presentation skills not piano grade 8). A rest mark tells a musician to pause for a period of time to let the previous note die away. To echo into the distance. To be savoured to the very last decibel. And so you should pause for effect in your presentations. Carrying on before the audience has properly understood and appreciated your previous point is to cheapen that point. A tip here. A short pause for the audience can seem like an eternity for us presenters – especially if we’re nervous in which case silence can really spook us. So in order not to under do the pauses count to five in your head in one thousand chunks before moving on.

“One thousand. Two thousand. Three thousand. Four thousand. Five thousand.”

In summary, the human voice is a musical instrument. So play it like one. And if you feel the audience may be getting bored listening to the same old instrument playing the same old song can you change the instrument (if not the song)? By that I mean can you change the presenter? Most presentations tend to have just one voice (you) but can you recruit co-presenters and double-head or even triple-head your next speech? The simple expedient of a change of voice can keep an audience attentive for longer.

Forgive me for a final foray into this musical metaphor. Make sure your presentations are well orchestrated. Be a maestro. Just like Mozart. Aim for a bravura performance.

This post was first published as a podcast (complete with extracts from Mozart’s Piano Concerto 21) in ACM Training’s Five Minute Masterclass series. You can listen to the original there or below.

[powerpress]