Captions are really good at making your videos more accessible. And handy for people who want to follow what you’re saying without having the volume turned up (even if it’s just in case the boss is listening). But it’s really annoying when those captions aren’t in the right place. The audience want to see your mouth. And your eyes. So here’s a bit of fun advice about positioning those captions so they help rather than hinder the whole business of communication. Yes! It’s the latest episode in the Z to A of Presenting.

Category: Communication

The Z to A of Presenting: T is for Tone

In this five minute video ACM Training’s communication coach, Richard Uridge, talks about striking the right tone in presentations – in particular in the current climate with all that is happening in Ukraine.

G is for Gimmick

Using cheap tricks or stunts to grab an audience’s attention is the presentational equivalent of click bait. So here ACM Training’s communication coach, Richard Uridge, explains (with just a hint of festive irony) the difference between gimmicks and legitimate devices to hook people into your presentation. And, yes, you really won’t believe what he looks like today!

How a treasury tag might have saved the Prime Minister’s bacon

Every failure is an opportunity to learn and grow – even when you’re the British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson. And it’s to him that we dedicate this episode of the Z to A of Presenting: T is for Treasury Tag. Watch to find out how the PM could have saved himself a whole heap of grief in that lemon-chewingly embarrassing speech to the CBI with one of those little bits of string with a tiny metal bar at either end that are buried at the back of stationary cupboards everywhere. It could just save your next presentation from a #peppapig moment too!

PS Buy shares in treasury tags!

[products limit=”4″ columns=”4″ skus=”wpid=145, bookid=02″]

Writing for the Web – now available on Apple Books

The first volume in ACM Training’s Wise Owl how-to series is now available in the Apple Bookstore. As an e-book only (for the time being at least) the publication of Writing for the Web – why reading differently means writing differently is not quite up there with the excitement I felt as my first front page lead thundered off an old News of the World hot metal printing press back in my days as a cub newspaper reporter. But hey, that’s the post-Gutenbeg era for you eh?! At only £4.99 in the UK and a similar price in 50 other countries I reckon it’s brilliant value for money. But then I would say that… I’m the author. Judge for yourselves and please let me know if you agree. Or not.

Things you can do with Zoom and never realised

We’re often asked how our Zoom and Teams meetings and training sessions here at ACM are funkier than most. So here’s the answer! Our chief geek (and media and communication coach) Richard Uridge runs through the kit we’ve put together to make our online courses visually stimulating.

[products limit=”4″ columns=”4″ skus=”wpid=145,bookid=01,wpid=142,bookid=02″]

The Z to A of Presenting: Z is for Zoom

The first in the “Z to A of Presenting” (because why start at A when everyone does)? In this Halloween-themed episode Richard Uridge explains how a simple sticky can help you keep your audience engaged. Watch to the very end if you want the full, scary surprise.

[products limit=”4″ columns=”4″ skus=”wpid=145,bookid=01,wpid=142,bookid=02″]

Ctrl copy ctrl paste | the two greatest enemies of creativity

Original writing is just that. Something new. Something that’s never been written before. And, by extension, something that’s never been read before. That’s not to say it’s any good. Original writing can be crap.

So why on earth would we want to use copy and paste? If the writing we’re copying is, indeed, crap we’re just adding to the dung heap. And if it’s any good we’re, at the very least, guilty of being unoriginal.

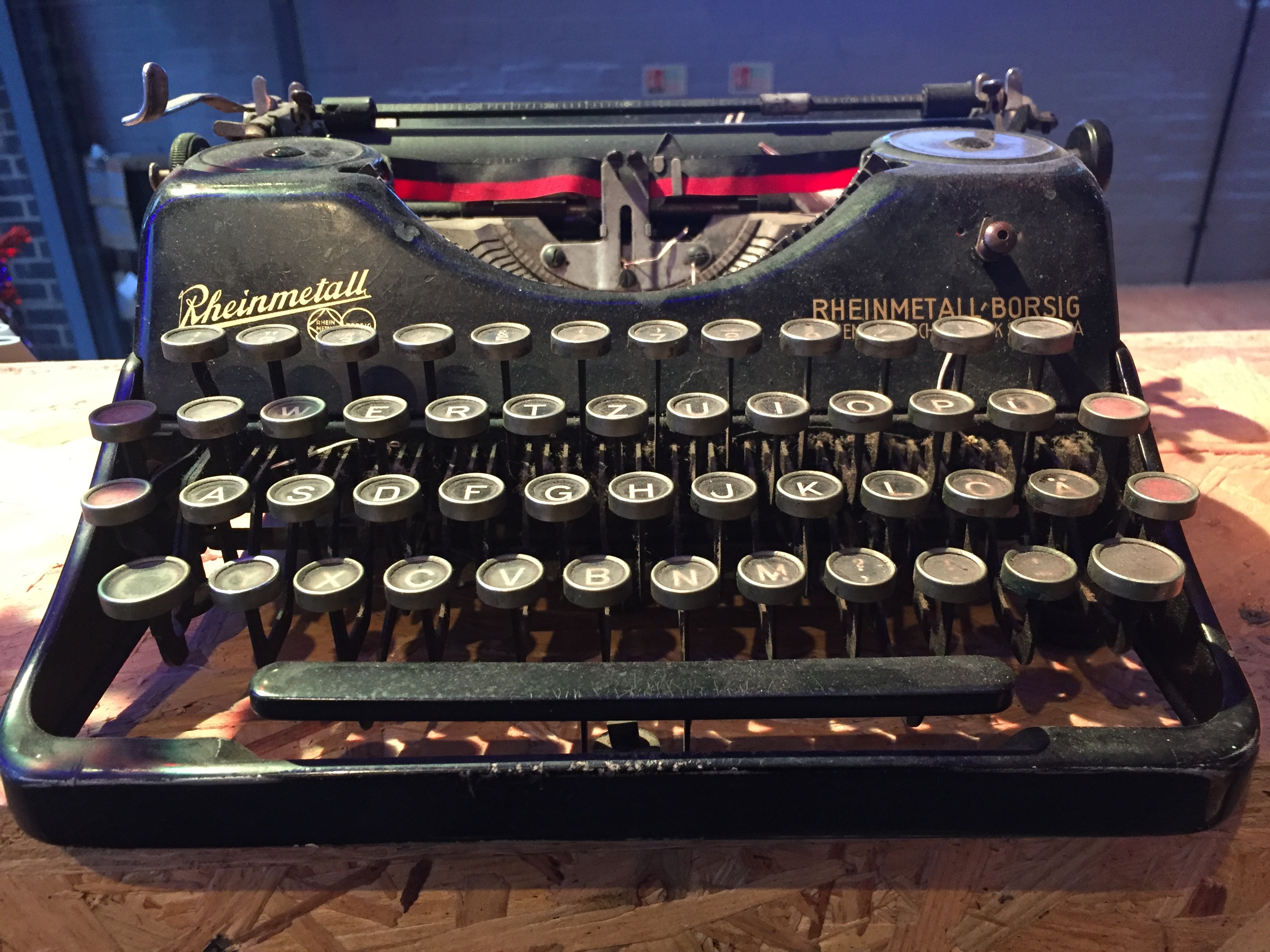

Whilst they have their uses those two keyboard shortcuts stifle creativity. So use them sparingly. Or, as this article in the Guardian suggests, be more like the actor Tom Hanks and use a typewriter instead.

[products limit=”4″ columns=”4″ skus=”wpid=145,bookid=01,wpid=142,bookid=02″]

Wheely armed webinars? I hate them!

A lot of presentation skills trainers are saying we need to be much more animated presenting online via Zoom and MSTeams than was the case when working face-to-face. In this short clip I argue against such an approach. I reckon the skills of an online presenter are more like those of a screen actor than a stage actor. Smaller, more suble movements and facial expressions are the key. Not grand gestures for the people in the cheap seats at the back of a theatre auditorium. Why? Because you are in their face. Or certainly no further than an arm’s length away.

Don’t start with content when planning a presentation. It ain’t the first step!

Step away from the PowerPoint. Close the Keynote. When you’re preparing a presentation – online or face-to-face – resist the urge to start creating content too soon. It’s a receipe for failure. And a mistake too many of us make.