Approx. listening time: 30 minutes

Richard Uridge discovers if bricks and mortar have finally had their day and asks what the future holds for the construction industry.

This podcast was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

Approx. listening time: 30 minutes

Richard Uridge discovers if bricks and mortar have finally had their day and asks what the future holds for the construction industry.

This podcast was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

Approx listening time: 28 minutes

The North Sea is a baby in geological terms. Before it was born at the end of the last Ice Age Britain was joined to the rest of Europe. Conventional wisdom says by a land bridge. But a student, searching through seismic data discarded by oil companies, has discovered what archaeologists believe is the best-preserved prehistoric landscape in the world. Richard Uridge dives to the seabed in search of evidence that’ll force history textbooks to be rewritten.

This podcast was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

Approx listening time: 14 minutes.

In the last of his current series celebrating Clever Trees Richard Uridge visits the National Arboretum at Westonbirt in Gloucestershire – with 18,000 specimens a veritable tree university – and talks to the trees.

This podcast was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

Other episodes in this series:

Approx listening time: 14 minutes

In the fourth of his programmes on Clever Trees Richard Uridge visits the Lost Gardens of Heligan in Cornwall where he finds a relative of the culinary bay that’s so potent it can give you a headache and another trees that’s smart enough to provide the cure.This podcast was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

This podcast was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

Other episodes in this series:

Approx listenning time: 14 minutes

Of all the clever things that trees can do telling the time has to be one of the smartest. This week Richard Uridge travels to Malaysia in search of the Simpoh, a tree which according to legend, flowers at precisely the same time every day.

This podcast was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

Other episodes in this series:

Approx listening time: 14 minutes.

In the first of five programmes on arboreal “intelligence” Richard Uridge visits George Washington’s home at Mount Vernon to meet two conjoined holly trees .

This podcast was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

Other episodes in this series:

Approx listening time: 14 minutes.

In the second of his programmes celebrating clever trees, Richard Uridge travels to Australia to investigate two apparent paradoxes: the tree that’s wet when it’s dry; and the clever idiot tree.

This podcast was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

Other episodes in this series:

Approx. listening time: 25 minutes

Richard Uridge presented Open Country on BBC Radio Four for almost a decade. In this programme he visits the Aran Islands off the coast of County Clare in Ireland. Beware – you’ll want a Guinness after listening! This programme was first broadcast in March 2004.

This is our social media policy at ACM Training. We’ve seen some longer ones in our time. Like the BBC’s social media policy where our social media trainer, Richard Uridge, used to work. He confesses he’s never read it. And that’s one of the problems with long and complicated policies. Nobody reads them when they really should. It’s a bit like the “mind the gap” warning on the railways. Short, sharp and to the point. Take too many words to say the same thing and people plunge to their (social media) deaths.

This is our social media policy at ACM Training. We’ve seen some longer ones in our time. Like the BBC’s social media policy where our social media trainer, Richard Uridge, used to work. He confesses he’s never read it. And that’s one of the problems with long and complicated policies. Nobody reads them when they really should. It’s a bit like the “mind the gap” warning on the railways. Short, sharp and to the point. Take too many words to say the same thing and people plunge to their (social media) deaths.

So if you’re contemplating posting a picture of a cat that looks like Donald Trump to your Facebook page – don’t. That’s banned under rule one. And, come to think of it, the others too!

If you’re in the process of drawing up a social media policy for your organisation we’d love to help.

[products limit=”4″ columns=”4″ skus=”wpid=78″]

I’m a big fan of diaries. Leather-bound analogue or online digital, they’ve saved my (personal) life more than once. Reminded me of children’s birthdays when there was still enough time to get presents. Helped me remember the exact day I met my wife so that the flowers arrived on the actual anniversary because a day late…well that bunch of tulips may as well have been Triffids. Stopped me missing the deadline to get those Christmas cards in the post to relatives Down Under.

And so content calendars can be (professional) life savers. Reminding us in plenty of time to plan and schedule content before it’s too late to post – not to Australia – but to LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter and the other places we’re colonising as part of our social media empires.

A content calendar should be the number one tool in your social media tool kit. It helps you plan and schedule your content across the full range of your platforms in advance.

The sheer volume of content on the social web means it’s getting harder and harder for your content to stand out. And to make matters worse organic reach is in decline. So to tackle these twin challenges you need to generate creative content, schedule it well and consistently and boost it selectively as your budgets allow.

Consistent posting is one of the best ways to get more followers. Regular updates show potential followers you are, in fact, worth following. That they’ll be rewarded with fresh and interesting stuff – whether that stuff is pictures, videos or words (written in a blog post or spoken in a podcast).

A content calendar can you help you achieve this consistency across your platform mix by getting you into the habit of planning and scheduling in advance and not missing opportunities. I’m guilty – and I’m sure I’m not alone – of forgetting my Twitter feed, for example, and then playing catch up by posting heaps over a short period.

The temptation is to use social simply to “sell.” Don’t! Many a sale has been lost by the seller being too pushy (think getting pounced on by an over-eager assistant the moment you walk into a shop). Pushy on social is understandable. After all, you’re putting a lot of time and effort into it and you want the best possible ROI. But, paradoxically, the harder you try to sell in an obvious way the less well you’re likely to do. Too much self-promotion can alienate your “customers.” The answer is to mix the explicit sales stuff with other content.

Eighty/twenty (80/20) is a good starting point. That is for every post that’s “selling” your product or service you make sure there are four posts that are helpful and interesting.

Another starting point is to use what’s called the rule of thirds. A third of your posts promote your business or generates leads. A third comes from other sources within your sector – on the understanding that your customers aren’t just interested in you and your company or organisation but have wider interests. And a third of posts engage directly with followers – for example, by answering their questions, responding to their comments or posting user-generated content.

Whichever approach you adopt, over time you’ll discover the exact mix between these sources that works for your business. A content calendar will help you stick with the right mix.

The simplest content calendars are those that come with your computer, tablet or smartphone. Just jot down ideas as you get them. They might be timeless ideas or have a long long “shelf life” in the sense that it doesn’t really matter if they’re posted this week or next month. Others might be date-related – tied to a particular day or event such as national bring your dog to work day (yes, really)!

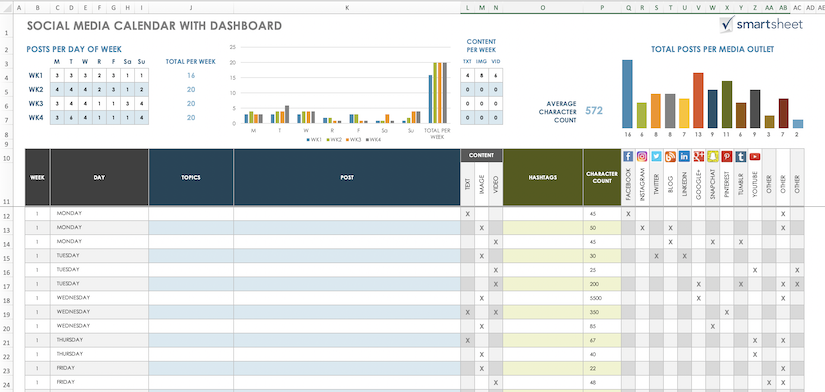

The more sophisticated calendars are spreadsheet based and can help you keep an eye on things like content quantity and network mix, with colour-coded pie charts and bar graphs. You can even add columns to assign work to colleagues or link to resources such as word documents, images and videos. Here’s one I’m road testing for a client courtesy of Smartsheet. It’s a free resource and seems pretty impressive so far, although I’ve only done a few miles so far so to speak.

Whatever calendar option you choose, encourage collaboration by sharing it via the cloud – unless it’s an old-fashioned wall planner which has the simple virtue of being seen by everybody who walks past it whether they want to or not.

You might think it’s a lot of faff filling in a content calendar and making sure it’s up to date. But used well it’s a time saver not a time waster. And the time you save can be re-invested in the all-important business of content creation. Remember content is king. Without good quality content and plenty of it you’re bound to fail!

Here are three other content calendar tips…

Finally here’s my content calendar entry for tomorrow: start blog post on quantity versus quality – why posting rubbish is drowning out the good stuff. And here’s my diary entry: order Christmas turkey.

[products limit=”4″ columns=”4″ skus=”wpid=78,wpid=63,wpid=109″]